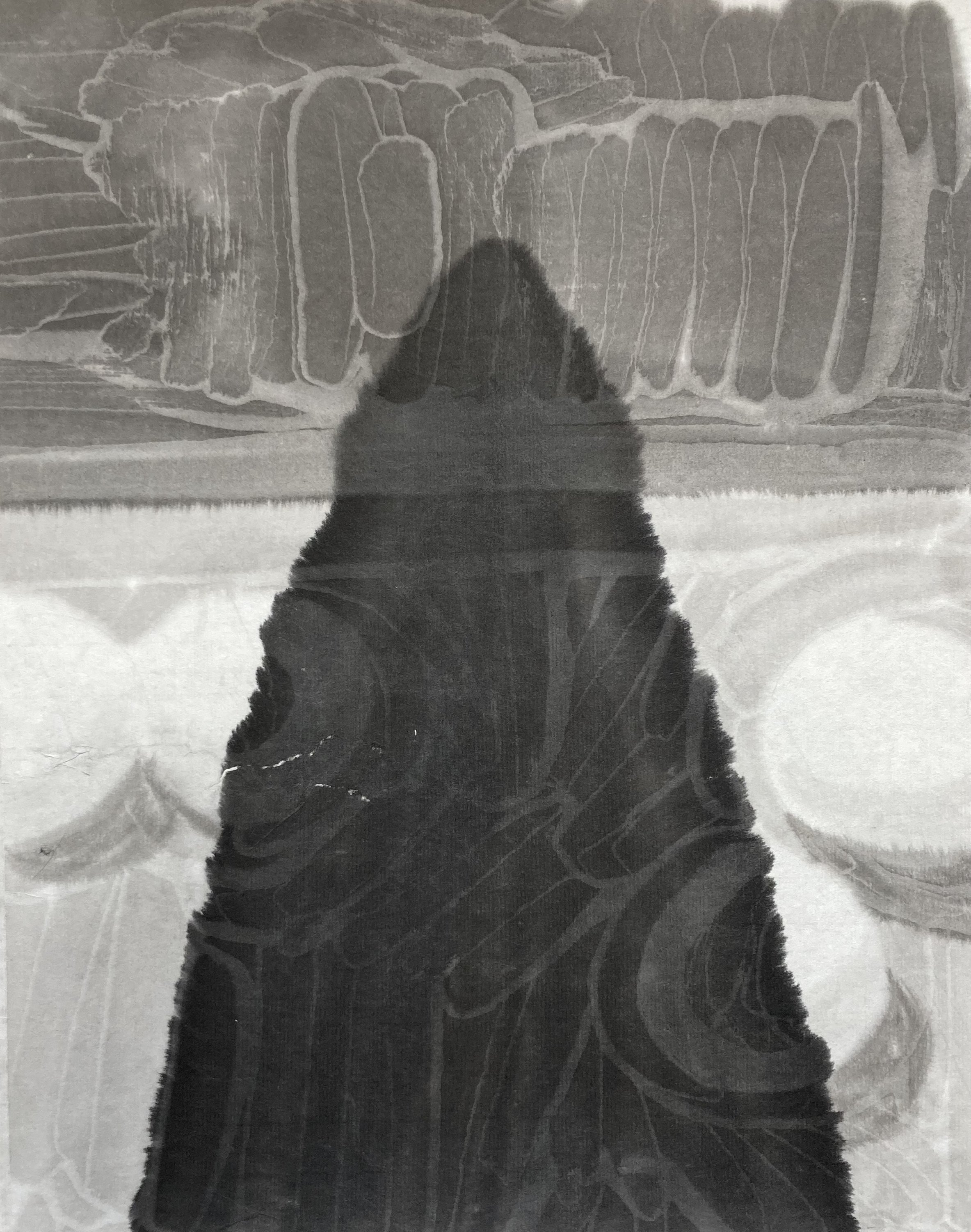

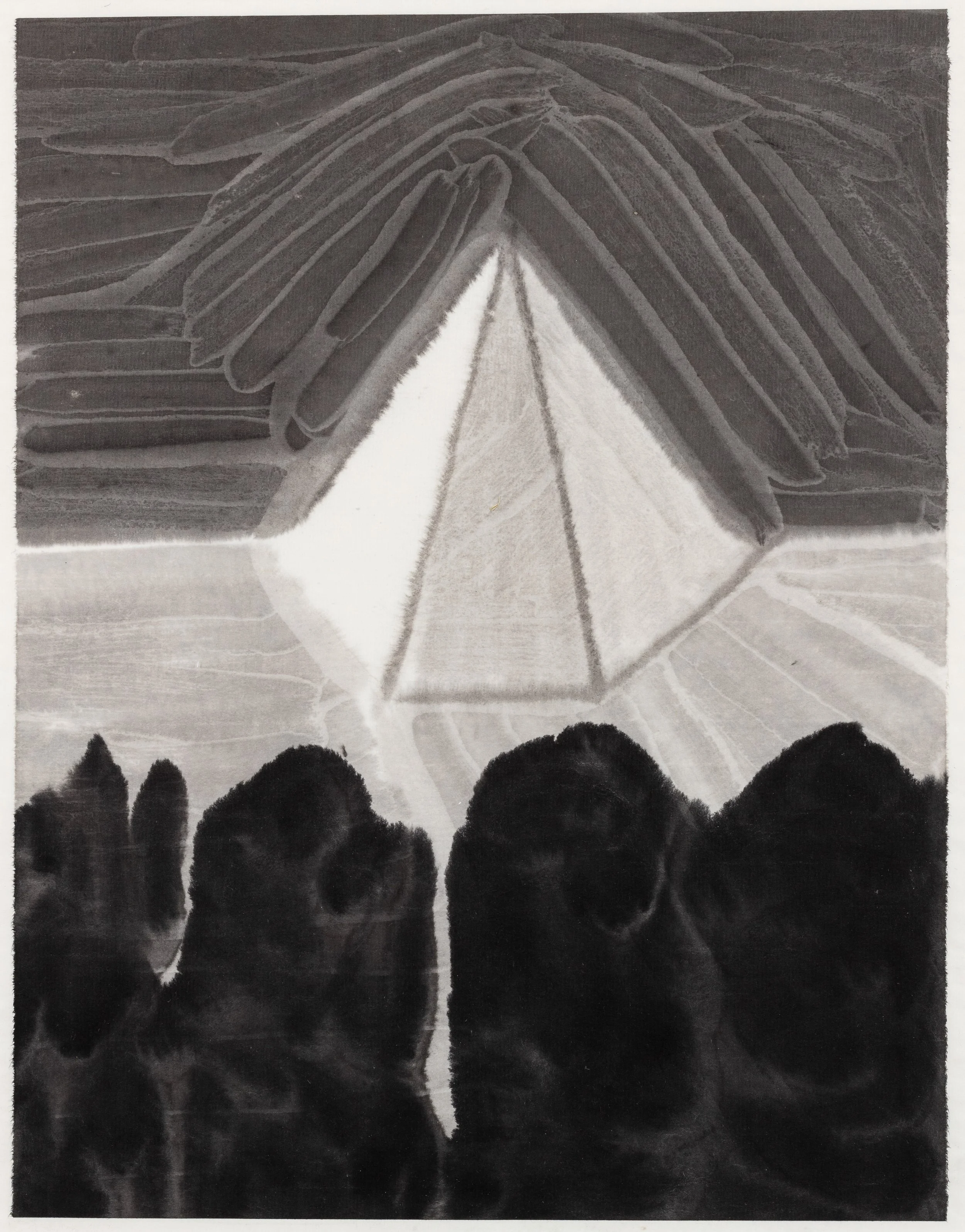

Raphael Egil, Untitled (from Beijing Diaries), 2013. Chinese ink on paper, 39 x 30 cm.

Studies and Exercises

Balthus, Alvaro Barrington, Raphael Egil, Petrit Halilaj, Gabriel Orozco, Sigmar Polke, Kaoli Mashio, Dorothea Stiegemann, Yoshifusa Utagawa

15th June - 27th August 2022

CLICK HERE to request a copy of the exhibition catalogue

What a mess! This is an exhibition of works that have neither very much in common nor so little in common that their clashiness is a conceit. There are works made in Europe, Latin America and Japan by artists born in Europe who are working in Asia and artists born in Asia who are working in Europe, but it is not such a broad diversity that the group could be called global or even particularly sprawling. There are works by the living and the dead, but the span of time from the 19th century to the present is not such an enormous stretch. The inevitable pareidolia induced by such a mess is not really groundbreaking or interesting.

But, in the end, I think there is still something good to be gained from an exhibition like this. There’s a line from Rimbaud: ‘a poet makes himself a visionary through a long, boundless, systematised disorganisation of the senses.’ Why should every exhibition need a direct line, an internal logic or cohesion? Duchamp always wanted chance to do some work, to be able to not take a position, to not choose. Sometimes it is useful for an exhibition organiser to be dictatorial in their approach, to say ‘this is what this exhibition is about and this is the arc I want the viewer to experience as they go through it,’ but that approach is quite removed from the full and true experience of making or looking at a work of art, which is always more of a half-formed, unclear and unresolved mess like this. Even when an artist or a viewer does set out with intent, with a clear idea of what they are trying to say and do or see, they can not possibly know in full the infinity of influence and experience playing out in their heads and in their bodies. Nor, perhaps, should they: Raphael Egil once said to me that if he knew completely what he was doing when he set out to make a painting then the work would probably be terrible.

This spirit of derangement and incoherence sits at the heart of this presentation in the form of Egil’s Beijing Diaries, a body of work made during a two month artist residency in the Chinese capital that is here presented as a kind of ‘exhibition-within-an-exhibition’. Egil is a masterful painter but fundamentally a European one, one who understands how European paints work, the relative densities and fluidities of oil, tempera and acrylic, the ways they mix, coagulate or settle on one another. He knows well the history of Western art, how to ‘read’ its paintings, and also its vertical structures of making and display: canvases are painted on an easel and transferred to a wall, where they hang untouched by anything but the gaze of their viewers, who ideally stand squarely in front. These systems are the structural conditions of European painting, they are the givens before work begins, and Egil was far away from all of them in Beijing.

In China, painting takes place perpendicularly to its European counterpart, flat on the ground instead of standing on an easel. The qualities of the paper are of great importance, and the work is not considered complete until it is mounted on thicker paper or on elaborate silk-embroideries. Paintings tend to be rolled rather than hung, or are kept in drawers. Viewing means handling them with careful fingers, images and narratives revealed in the literal unfurling of long scrolls. There is a history of Chinese painting that has little or nothing to do with European art, and which Egil had no knowledge of at all: it was even hard for him to say which works were recent and which were five hundred or a thousand years old. The Chinese ink that a friend introduced him to acted differently to anything he knew, the paper worked on wet and each brushmark forming a quick barrier at its edges, resisting rather than blending with the marks around it. This is the ink that was used to make Beijing Diaries, a series of around 60 works that each document the artist’s impression - literal or abstract - of another day in Beijing. For Studies and Exercises, these Diaries are presented alongside a landscape garden of preparatory studies in Chinese ink, placed like paving stones on the floor, where you can see the artist trying to work out the physical and technical qualities of the medium.

The example of this body of work though, which began in a position of such estrangement from the artist’s usual structures and comforts, is just an extreme example of what perhaps ought always to be true when an artist sets to work, and which is a phenomenon that is particularly evident in works on paper: it is the things the artist doesn’t know that make the work alive more than the things they do know. Preconceived ideas on form and content are all very well, but the parts of a painting or work on paper that bring it into the living world, that make it magical and alchemic, that make it breathe, happen in the process of its making, in the working out rather than the concept. A painting without any momentary lapses, without any hand of chance or changes in its working, is only static, illustrative, just a graphic. And works on paper, with their intimacy and proximity to the artist’s hand as it studies through the process of exercise, might bring us closer to this phenomenon than any other medium.

So that is why I wanted to present this mess of an exhibition, not because it has any line or lines but because it has none, and because that is affirming in itself. Galleries are always trying to outdo themselves, powering relentlessly from one groundbreaking exhibition to the next, but here we take a beat and a breath, because that is also worth doing. I am thinking of Duchamp again, and his great answer to the question of what he had been doing with his time since his supposed retirement from art making: ‘Oh I am a breather, a respirateur, isn’t that enough?’.

Fraser Brough, Director, CASSIUS&Co.

Balthus, 'Nu Assis (Michelina)', 1976. Pencil on paper, 40 x 30 cm.

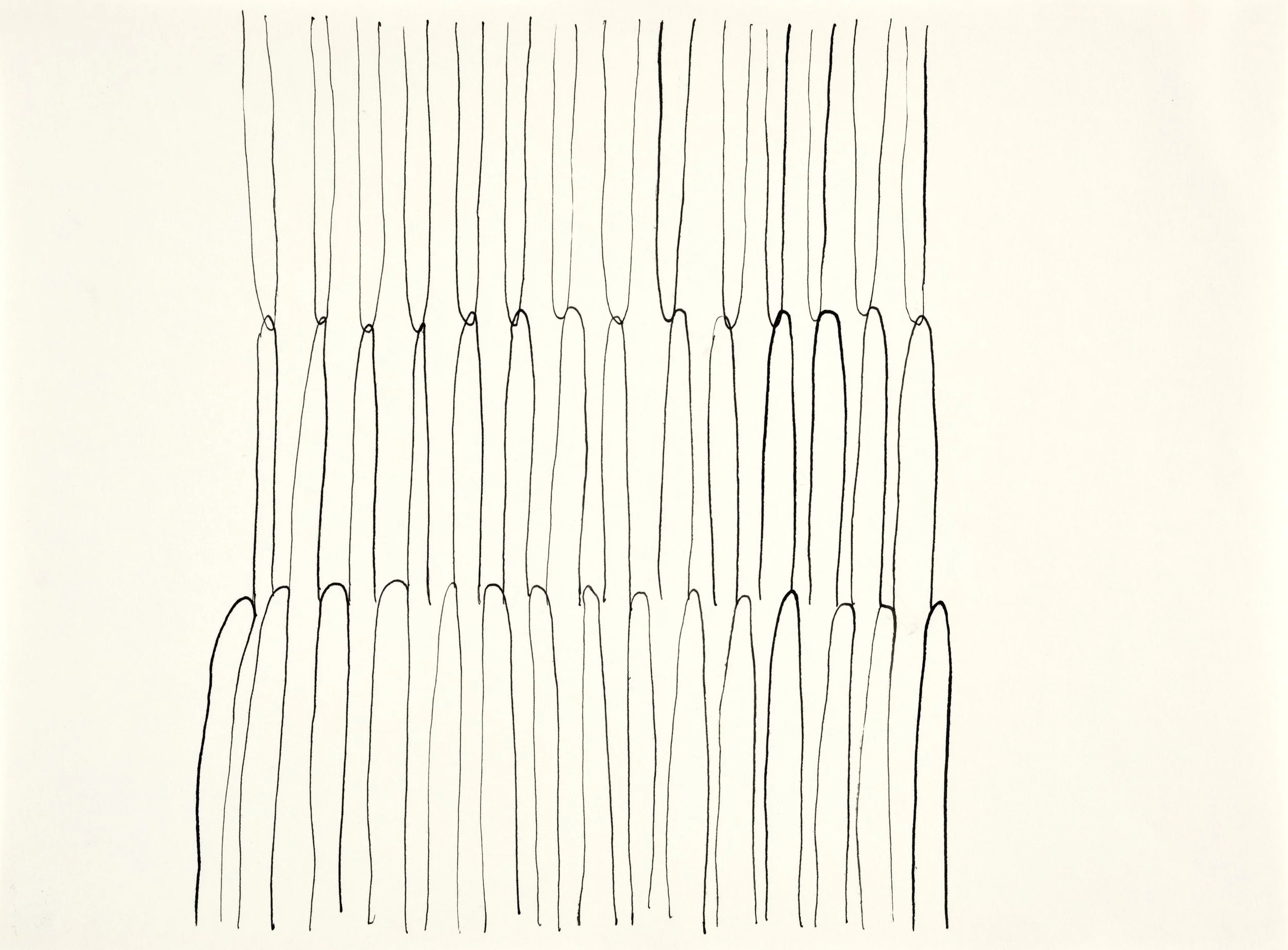

Kaoli Mashio, 'Untitled', 2020. Ink on paper, 21 x 28.4 cm.

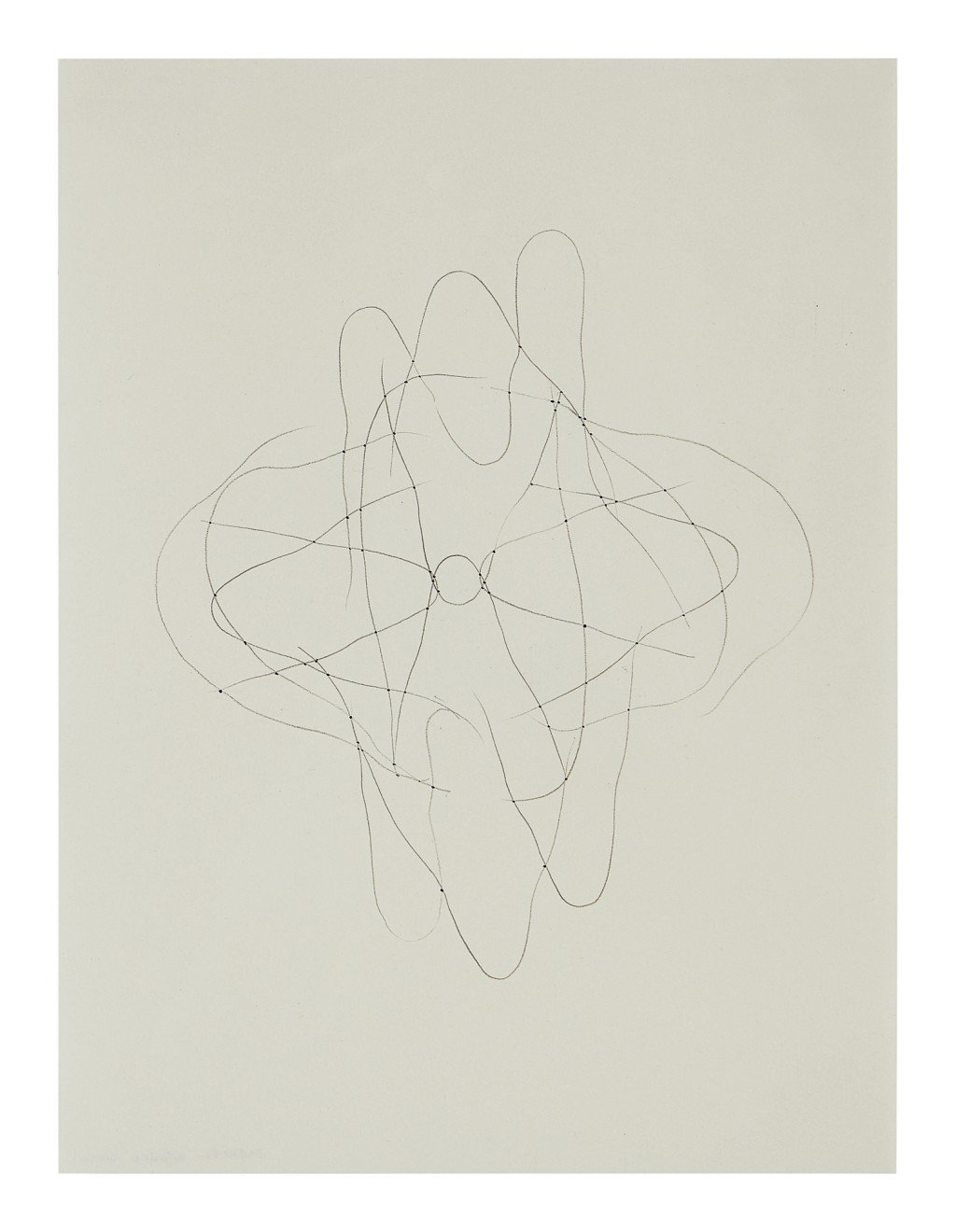

Gabirel Orozco, 'Untitled', 2002. Ink and graphite on paper, 28 x 21 cm.

Yoshifusa Utagawa, 'The Ghost of Akugenta Taking Revenge on Nanba at the Nunobiki Waterfall', pub. 1856. Woodblock-printed triptych, each sheet 37 x 25 cm.

Clockwise from top left: 1. Balthus, Étude pour ‘Nu sur une Chaise Longue’, 1949. Ink on paper, 31.5 x 24 cm. 2. Kaoli Mashio, Wave, 2022. Indian ink, collage and gouache on paper, 41 x 32 cm. 3. Dorothea Stiegemann, Untitled, 2015. Gouache on paper, 35 x 24 cm. 4. Sigmar Polke, Untitled, c. 2000. Spray-paint over computer print, signed in pencil. 35 x 28.5 cm. 5. Kaoli Mashio, Kaoli Mashio, Flag, 2022. Gouache and collage on paper, 38 x 50 cm. 6. Dorothea Stiegemann, Untitled, 2015. Gouache on paper, 29 x 26 cm. 7(centre). Balthus, Nu Assis (Michelina), 1976. Pencil on paper, 40 x 30 cm

From top: 1. Alvaro Barrington, 1943 - 1966 (9). Oil and acrylic on burlap paper in artist’s frame, 27 x 36.5 cm. 2. Dorothea Stiegemann, Untitled, 2017. Ink on paper, 29 x 41 cm. 3. Kaoli Mashio, Untitled, 2020. Ink on paper, 21 x 28.4 cm.

Clockwise from left: 1. Gabriel Orozco, Untitled. Ink and graphite on paper, 29 x 21 cm. 2. Yoshifusa Utagawa, The Ghost of Akugenta Taking Revenge on Nanba at the Nunobiki Waterfall, pub. 1856. Woodblock-printed triptych, each sheet 37 x 25 cm. 3. Petrit Halilaj, Moth #4, 2017. Artist’s frame, Killim Carpet from Kosovo, black ink on paper and metal pins,120 x 60 x 5.5 cm. 4. Kaoli Mashio, Wellblech, 2020 (three works). Oil and wax on paper, each 28.4 x 21 cm (motif: 15 x 15.5 cm).

L-R: 1. Dorothea Stiegemann, Untitled, 2017. Oil on paper, 41 x 29 cm. 2. 1. Dorothea Stiegemann, Untitled, 2017. Oil on paper, 41 x 29 cm.

Raphael Egil, Beijing Diaries and Studies for Beijing Diaries, 2013. Chinese ink on paper, installation view.

Raphael Egil, Beijing Diaries and Studies for Beijing Diaries, 2013. Chinese ink on paper, installation view.

Raphael Egil, Beijing Diaries and Studies for Beijing Diaries, 2013. Chinese ink on paper, installation view.

Raphael Egil, Studies for Beijing Diaries, 2013. Chinese ink on paper, installation view.

Raphael Egil, Beijing Diaries and Studies for Beijing Diaries, 2013. Chinese ink on paper, installation view.