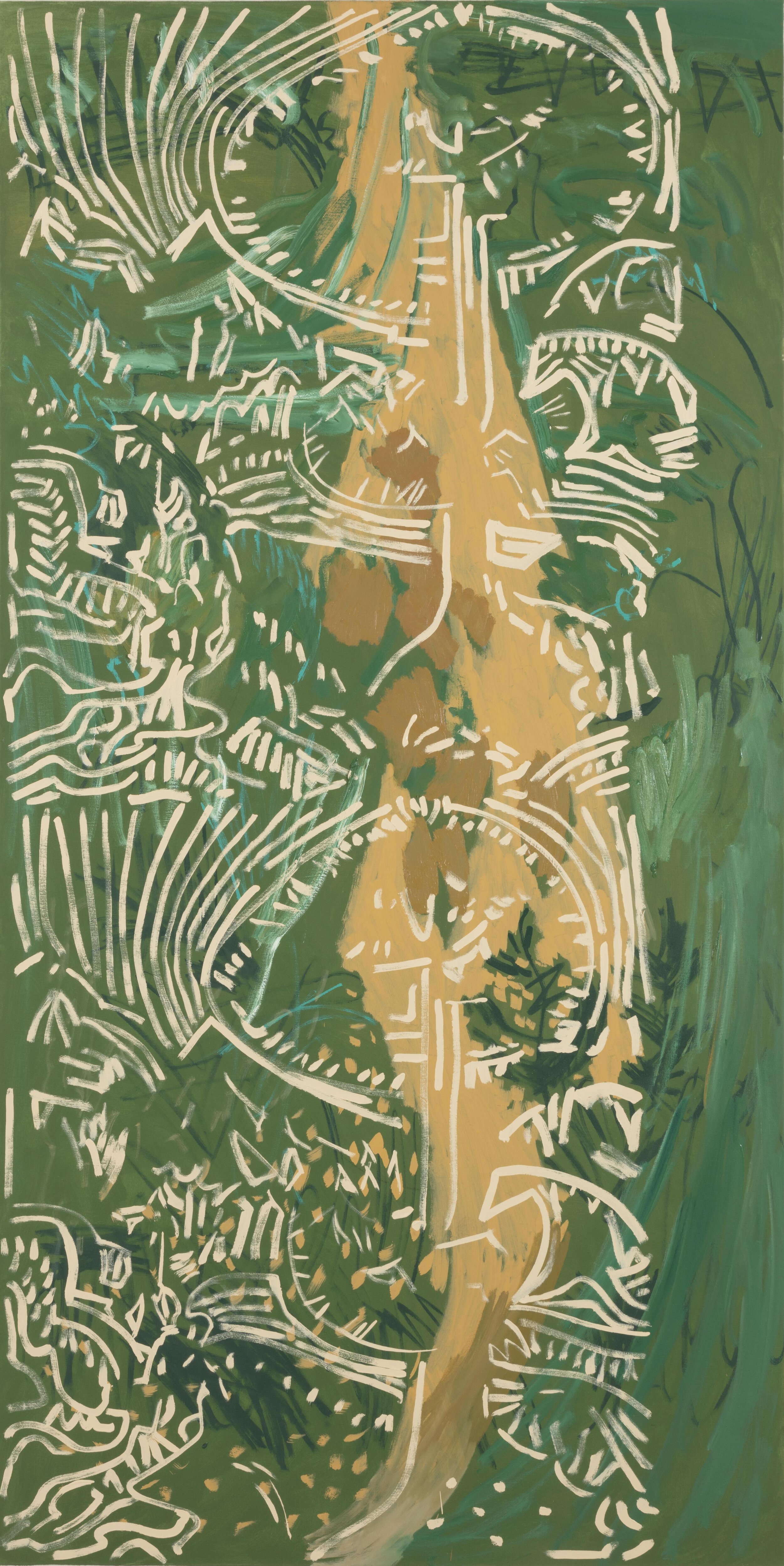

Raphael Egil, Gegenhang, 2020. Oil on canvas, 242 x 122 cm.

Raphael Egil

Paintings

12th April - 24th July 2021

CLICK HERE to order the exhibition catalogue

In 2018, the art dealer Michael Werner received a letter out the blue from a man he had never heard of. Letter, actually, is not the right word. Letters begin with ‘Dear Mr Werner’, they have preambles, well-wishes, justifications, and ‘yours sincerely’ at the end. The only text included in this message was a name, Raphael Egil, along with a return address. Instead, what he had received was a packet of images, images of paintings, unsolicited, unjustified and without explanation. Images that, on their own, were enough to compel him to respond.

Raphael Egil lives quietly, somewhere outside of Lucerne, and spends most of his time painting. That he included no text in his envelope to Michael Werner was less a sign of confidence in his own abilities than his belief in the power of painting in general, and its capacity to say things words can’t. The near-immediate response he received from Michael Werner was a source of great and happy surprise.

For this exhibition, the artist’s first solo showing outside the German-speaking world, Egil is presenting a group of works that form a painterly spiral between himself, that is, his mind and his body or his inner and outer existences, and two of his artistic heroes: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Paul Cézanne. I use the word spiral instead of circle because this is an open circuit, not a closed one, with room for new influence and change. It is a spiral that is at once formal, conceptual and poetic, and it is one which does not translate well or easily into words. But I will try.

Egil has said that he loves the rhyming in paint of the white bodies of the women in his versions of Cézanne’s Bathers with the white lines of the mountainous landscape he has taken from Kirchner’s woodcut Der Baum (1920). It is a curious rhyme. The version of Cézanne’s Bathers that Egil has repeatedly transcribed here (which was for a long time owned by Henri Matisse), is a work that is primarily about the act of touching, intimacy, Cézanne’s simultaneous desire and incapacity for it, his anxiety and his lust. It is a picture that luxuriates in the thought of naked female bodies in nature, but in which no actual touching can be discerned - intimacy breaks down every time you think it is getting close. It is a picture about longing for things outside the self but which consistently fails to connect with them. Kirchner’s Der Baum, on the other hand, transcriptions of which also abound in this show, was made at a moment when the artist, recovering in the mountains from morphine addiction, was throwing himself into the natural world, finding solace and support in the landscape, the exterior, where previously he had searched only in himself. He is succeeding in the very thing Cézanne is here failing at. In Kirchner’s woodcut, one almost doesn’t notice the two figures walking, so completely are they integrated into the line structure, into the all-encompassing glory of the mountains.

Another rhyme repeated in these works is in the relationship between the changing blue sky in Egil’s Bathers and the haunting blue tree that appears again and again throughout this exhibition, and which was sourced from another Kirchner work, Der Blaue Baum (1920). It is the loop which joins up the spiral. In the Kirchner painting we see a forest at night, dark and haunting apart from a bright blue tree that is glowing in the middle of the picture, and which Egil has described as being an image of the artist’s inner existence. The sky behind these bathers is shifting constantly, looming and receding in its shades of blue just like Kirchner’s tree. Is that sky its conceptual and painterly opposite, an image of the changing, external world?

In Landschaftsbild I, Egil has said that he set out to make a landscape painting in which the sky doesn’t serve as the receding background, but rather is the picture’s focal point, set right at the front. This formal manoeuvre has here, poetically, and quite unintentionally, become another haunting blue tree, the blue tree of Kirchner’s Der Blaue Baum. And in Ohne Titel, we see a patch

of blue that began as a blue tree in an earlier painting, one now covered over with a white sky that is heavy with its memory, and where it now seems caught in an unending spiral between flat square and blooming sphere. This type of shifting ground,

where the formal becomes the evocative, the academic becomes the prosaic, is perhaps where the magic of this exhibition’s spiral can be sensed most strongly.

I have used the word transcription several times in this text, but on close inspection there is not a single line in any of these works that can be accurately traced back to the originals, not a single mark that has been faithfully copied. And the fact that these canonical images overlay images of Egil’s own making, sometimes with both sets of information visible, other times covering each other completely, means that all of these paintings are palimpsests in greater or lesser states of resolution, all-at-once presentations of compounded, overlaid visual information. Egil’s own creations and the works of these masters persist in this constant tension, neither cancelling the other out, neither superseding nor submitting. Perhaps rhythm is a better word than tension, the images looming and receding like the rising and falling of music.

I have mentioned that in Kirchner’s woodcut Der Baum there are originally two figures walking in the hills, but these men do not appear in Egil’s versions. He has said that figures, however much he might like to include them, tend to introduce a narrative to his pictures and that is not something he wants. And yet, in the alpine lines that make up the image, each one of which can be seen as a mountain, figures do begin to form - one sprawled at the foot of the tree, for example, elsewhere a hunter in the snow. These are paintings that always have more to discover in them, more images to find inside. And in this way each of these paintings is its own spiral, a vortex that only gets deeper the more time you spend looking. Like Egil himself in his letter to Michael Werner, I have found it impossible to write fully what I feel about them, because they get to a point in painting that goes beyond my capacity of language. But looking at them deeply and then deeper still I find that I too can put faith in the power of painting without explanation, justification, or anything more than itself.

'Ohne Titel', 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 120 x 150 cm.

'Badende III', 2020. Oil on canvas, 45 x 45 cm.

'Landschaftsbild I', 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 30 x 40 cm.

'Baum', 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 40 x 30 cm.

'Blauer Baum', 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 190 x 160 cm

'Zwei Bäume', 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 45 x 78 cm

'Badende I', 2020. Oil on canvas, 45 x 45 cm

'Blauer Baum', 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 40 x 37 cm

Blauer Baum, 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 190 x 160 cm.

L-R: 1. Ohne Titel, 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 120 x 150 cm. 2. Badende III, 2020. Oil on canvas, 45 x 45 cm.

Zwei Bäume, 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 45 x 78 cm.

L-R: 1. Reusszopf I, 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 100 x 130 cm. 2. Badende V, 2020. Oil on canvas, 45 x 45 cm.

Gegenhang, 2020. Oil on canvas, 242 x 122 cm.

Ohne Titel, 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 45 x 78 cm.

Badende IV, 2020. Oil on canvas, 45 x 45 cm.

L-R: 1. Baum, 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 40 x 30 cm. 2. Blauer Baum, 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 190 x 160 cm.

Blauer Baum, 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 40 x 37 cm.

Ohne Titel, 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 120 x 150 cm.

L-R: 1. Blauer Baum, 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 40 x 37 cm. 2. Badende I, 2020. Oil on canvas, 45 x 45 cm. 3. Ohne Titel, 2020. Oil and tempera on canvas, 40 x 30 cm.