Hardy Hill, Figure Facing Away, 2024. Drypoint, plate-lithograph, ink and white chalk on cotton rag paper, 35.5 x 28 cm.

Hardy Hill

Now it’s dark and there’s somebody in it

16th May - 31st July 2024

CLICK HERE to request a digital copy of the exhibition catalogue

If you drop an image of Hardy Hill’s 3 Figures in Photograph into altext.ai, a program that uses artificial intelligence to generate descriptions of images, it comes back with ‘a muscular man smiling and holding a saxophone.’ For Figure on Back 4 (sleep 6) it gives you ‘a person lying on a couch with their legs up against the backrest. The scene conveys a tranquil, serene mood.’ For 3 Figures, 1 with Face Covered (theater 6), ’two men sketched on paper, one standing and the other sitting.’ The inaccuracies are one thing, but how can this program fail to notice how utterly disturbing these works are?

For one thing, it does not ask itself ‘Why?’. Why is this figure covering another’s eyes while holding him up from behind? Why would a person be naked in a car in that specific position? It is hard to conceive of an innocent answer to these questions, though when I first saw 3 Figures, 1 with Face Covered (theater 6), I wrote to the artist saying that it looked like the servants of Gilles de Rais taking a child to his tower to be tortured and he replied ‘Get your mind out the gutter, it’s just a surprise party.’

There is nothing explicitly wrong going on in any of these works. The figures are smiling, holding clarinets, sitting in chairs, looking out of windows, and their titles, which sound as though they were written by a machine, are simply accurate. The slippage between what is literally shown and what is viscerally sensed is slight.

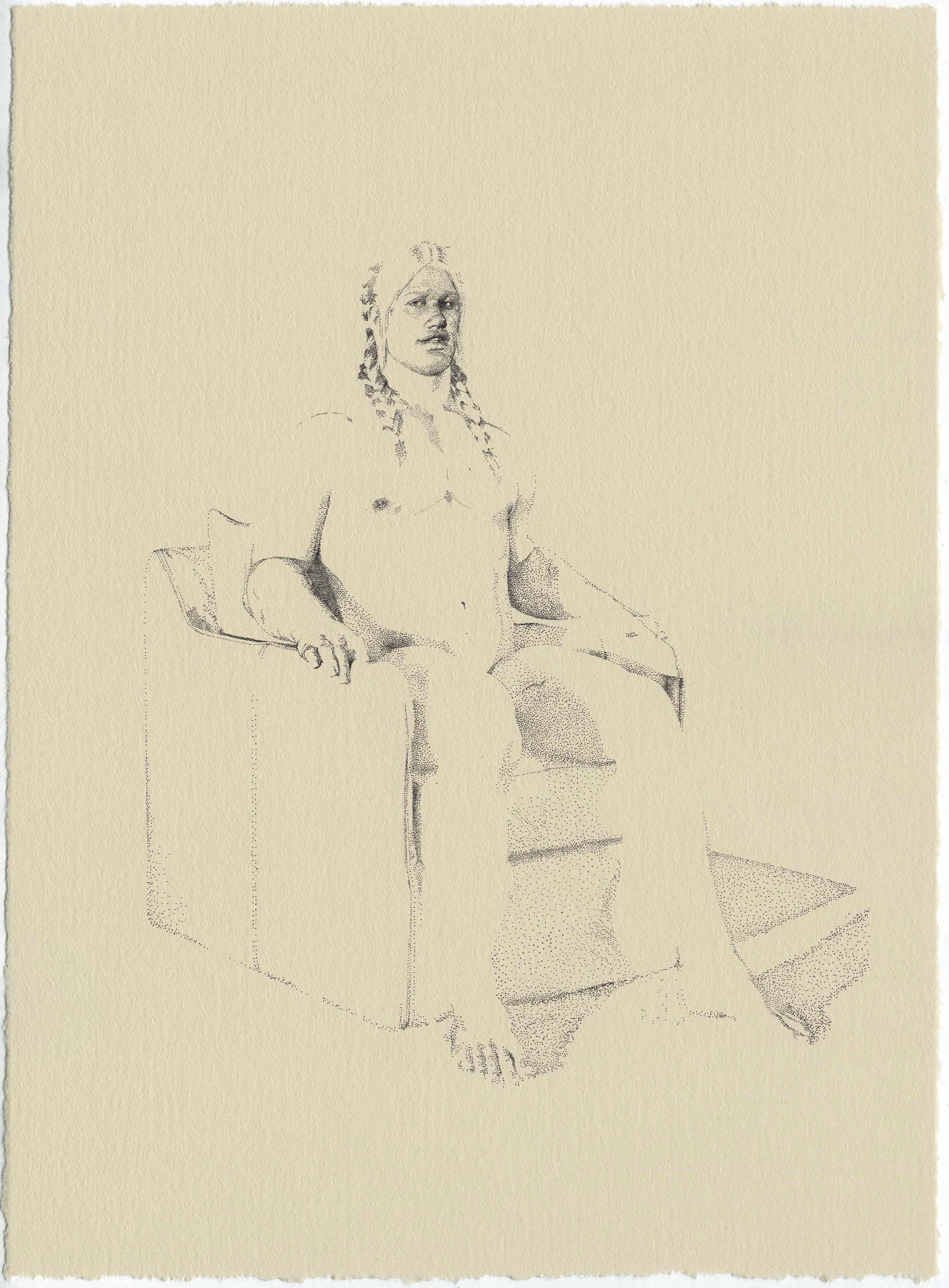

Take Seated Figure, where a bear of a body inhabits a seat that succeeds in being both specific and nondescript at once. The creepiness of the image has only a little to do with the figure’s nakedness; rather it is in the jarring way he sits, as though at odds with the chair, as well as the oddness of his haircut and the repellant look on his mouth, which has the transience of the Mona Lisa’s but with benevolence exchanged for perversity.

There are no real people in this exhibition, just figures, each as soulless as a doll. That they have been rendered with such meticulous attention makes them even more unpleasant, for you have to ask why anyone would make such horrible images so exquisite. The artist prints them with engraved copper but they are not editions, and when each is finished he cancels the plate, and touches the print up with pencil, chalk and gouache. I asked him why he doesn’t just make them as drawings - in the interest of time and money - and he answered that he enjoys the cruelty of the printmaker’s needle.

Hardy, I should say, is not a psychopath - he is about as lovely as a person can be. He studied printmaking at the Rhode Island School of Design before switching to Early Christian Theology, and has a wonderful knowledge of esoteric exegetes of the 2nd - 5th centuries with scrumptious names like Athanasios of Agrippa and Theophilus of Antioch. He is also a homosexual male with access to the internet, over which he exhibits a degree of mastery, and which, in an oblique way, provides much of the source material for his work: there is almost nothing imaginable that he has not seen. I mention this only because it is one of the things that puts him in a different position to queer artists of the last century, who first had the task of making visible their existence, not to mention their humanity, and indeed from queer artists more recently, the kind of painters making soft, languorous works describing their sexual lives. For me those have the same effect as the works of Raphael in the Florentine Renaissance; a kind of apogee, I suppose, but one that swiftly feels flaccid and dull for being too cookie-cutter perfect, too twee. Hardy Hill is a kind of Mannerist in this way, taking that line of queer image-making and twisting it for his own purposes, which are necessarily weirder, darker, and more stylised than what has come before.

There is another reason that the works in this exhibition are so sinister, which has to do with the way they are lit. The figures are bathed in a light emitted from the picture plane’s zero-point, ‘a kind of reconstituted Euclidean extramission’, to use the artist’s phrase. It is the light of a police torch, or a camera flashing in the dark. And the only person who could be holding it is you, dear viewer, the agent and the author of these image-crimes.

Now it’s dark and there’s somebody in it is an exhibition that will disturb you, but at least it will make you feel something. I think the main reason that a computer can’t see how creepy the images are is that it has never seen images like this before, which is an artistic achievement in itself. But more importantly, one has to have a capacity for empathy to notice when there isn’t any there, one has to have a human soul to see this. And in this way we could say that this exhibition is the most life-affirming ever held at this gallery.

'Seated Figure', 2024. Plate lithograph and ink on cotton rag paper, 35.5 x 28 cm.

'4 Figures in Group (examination 4)', 2024. Plate lithograph, chalk, and ink on cotton rag paper, 35.5 x 28 cm.

'Figure on Back 4 (sleep 6)', 2024. Plate lithograph, pencil, and white chalk on cotton rag paper, 35.5 x 28 cm.

'Figure in Field', 2024. Plate lithograph, ink and chalk on cotton rag paper, 35.5 x 28 cm.

'3 Figures in Photograph', 2024. Plate lithograph and pencil on cotton rag paper, 35.5 x 28 cm.

'3 Figures, 1 with Face Covered (theater 6)', 2024. Plate lithograph, dry-point, and chalk on cotton rag paper, 35.5 x 28 cm.

'Figure in Serpentine Posture', 2024. Plate lithograph and pencil on cotton rag paper, 35.5 x 28 cm.

'Figures in Yard 2 (theater 7)', 2024. Plate lithograph, dry point, pencil, and chalk on cotton rag paper, 35.5 x 28 cm.